004: Robin Hanson is Right & Everyone Else is Wrong.

The Future of Forecasting isn't where you expected.

Welcome back to Predictions. After a month apart, in large part due to the difficulties of natural disaster forecasting 😉, we return!

In this issue, we grapple with Robin Hanson’s speech from last month’s Manifest Conference on forecasting and prediction markets held in Berkley, CA, and the implications it has for the future of the space. Afterwards, we highlight the biggest articles about forecasting and prediction markets released in the past month.

❤️ Don’t forget to like the newsletter. It’s like a tip, but free!

🔁 If you loved the newsletter, please consider restacking it or 📧 forwarding it to someone who might enjoy it!

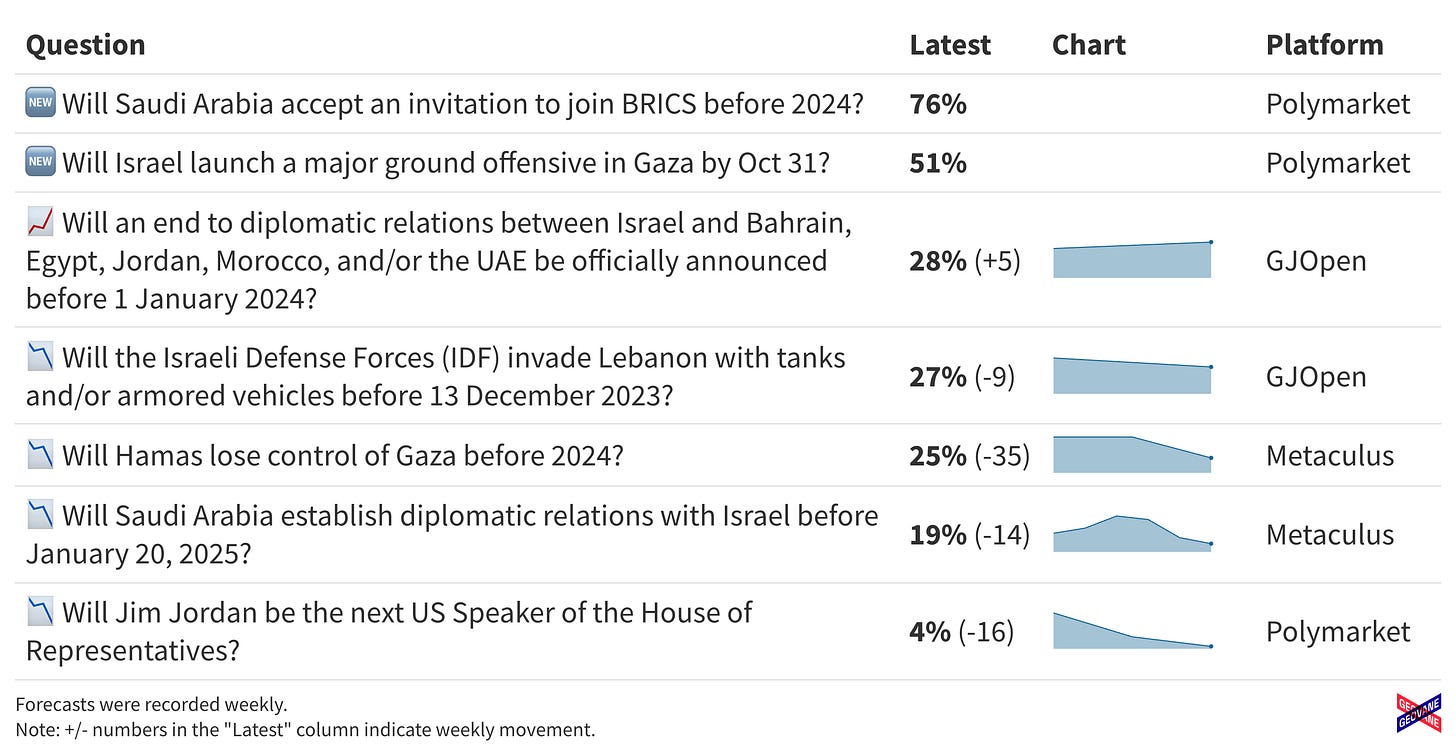

But first, the biggest news stories as told by prediction markets:

News in Numbers: October 21, 2023

RECORD YOUR PREDICTIONS

Do your own research! Explore diverse perspectives and stay informed with the world's largest news aggregator, Ground News. Sign up using this link to reveal the hidden biases behind every story.

Deep Dive: Is Robin Hanson Right about Prediction Markets?

What if Robin Hanson is right and everyone else has it wrong?

That has been the main thought percolating in our heads since we departed the Manifest 2023 Forecasting Conference in Berkley, California, and, to be clear, everyone else includes us!

At the conference, Hanson gave a speech which we entitled Take the Gold!

In many respects, however, Hanson’s address was less a speech and more a plea to those in the room. Directly addressing the founders of Manifold Markets in the audience, Hanson concludes his address by saying:

In prediction markets, in betting markets, there's gold in the hills. It's just the hills after the ones you're on.

But they're not that far away. And there's a lot more gold there than the gold nuggets you've been finding on this hill.

I mean, it's good that you went to this hill and got these nuggets—that's great. I agree. But, at some point, I want to inspire greed.

The hill over there, the next one over, it's got—you can even see them from here, take out your scope 🔭—big shining gold nuggets, glinting in the sunlight.

You just have to go through that valley, up to the other side, and take the gold!

So what is Robin Hanson getting at?

The Failure of Today

Prediction markets and the application of quantitative numbers and statistics to subjective probabilities has been around for a long time, predating our current century. Yet, even in the 21st alone, numerous companies have arisen trying to propagate the technology and none have achieved great success—there has been no forecasting nor prediction market unicorn.

With the exception of perhaps Good Judgment Inc., whose primary business comes from government contracts, as well as individual research projects with the intelligence community (which have seen limited real-world application), the preponderance of effort in this space has centered around attracting a mass of individuals to either trade on these markets—whether they be real money, fake money, or reputation markets—or to convince that mass that the information provided by these methods are less biased, more informed, and therefore worth your money.

But what if this is the wrong approach? (Or, as Hanson would interject, this is the wrong approach.)

The theoretical claims that these markets and methods provide real value are there. We’ve read the literature—just damn near all of it—and it paints a convincing picture. That’s why we are still here in the space after years! Yet the general population has yet to bite.

There are two possibilities for this:

The first is that tactical problems still remain. That despite all the companies which have risen and fall, and the decades and centuries which has passed, we still haven’t figured out the right UI/UX, or the right automated market maker to encourage trading and liquidity, or the right messaging campaign to bring awareness to the technology and its benefits. Or perhaps it is a regulatory problem which limits the number of markets bettors can play.

The second goes back to Kant, which says that the existing theory is not wrong necessarily, but that there just isn’t enough theory.

Perhaps we are missing something which complicates the picture, that prevents the rosy picture of prediction markets and forecasting in larger society from forming. Ethics and public sentiment on quantifying, speculating, and potentially betting on war, civil unrest and disruption, or contested and bitterly partisan elections? The limits of our understanding in both the hard sciences but especially the social sciences and what the means for the veracity of our predictions? The dominance of system effects and the limitations on what questions are answerable, and how that intersects with the questions the general population wants answered?

(And then there is also the uncomfortable reality that perhaps prediction markets just don’t deliver that good of information today because forecasting is hard and delivering true foresight requires an immense effort that is simply uncompensated by existing systems.1)

Some of this Hanson says explicitly, some of this was implicit, and some our own interjections into his comments. But to return to Hanson’s explicit argument, what if instead the best application of this technology—which excels at aggregating disparate information, reducing the bias of those involved, and encouraging accuracy and information gathering—is instead in areas where you only need to convince a small group of key decision makers about their value? Moreover, what if you were to focus on those areas which also had large amounts of savings or benefits delivered to marginal increases in accuracy?

Finding Value for Tomorrow

Hanson offered two such possibilities in Berkley—hiring and deadline markets for companies—and has written about others in the past, including college admissions and firing a CEO markets. These are as niche, high-value areas that he believes forecasting and prediction market companies should focus on.

In prediction markets, if I ask what are the biggest high initial value things, the thing that most often comes to my mind is new hires. Almost any organization with 20 people hires 2 to 4 new people every year…if not more.

—Robin Hanson, Take the Gold!

Hiring an employee is an expensive and important decision for a company. It is expensive not only because of the provision of salary, but also benefits and training. It is important because there is the risk of degraded team performance, particularly when dealing with higher-up positions and the C-suite in particular, as well as the uncertain opportunity costs when choosing between people.

In speaking with a leading executive search consultant, we learned that replacements for founders were only a good fit for their new company 50% of the time. They offer to do a replacement search if this is the case within the first 12 months, but most issues with hires are not noticed until 18-24 months. Not that great of a performance for such a consequential role, especially in startup companies where founders are particularly influential for company success!

So how could prediction markets or polls help?

For every new hire you consider, you might have different rounds, but in the last round you might consider three times as many people as you have slots…

You could do a prediction market in that last round of, for each of the people you’re considering this last round, if we hire them, what will we think of that choice in a year or two?…

And most organizations have the practice of having some sort of employee evaluation where you rate people…yearly. That fits straightforwardly into standard practice.

—Robin Hanson, Take the Gold!

As Hanson notes, this would require better systems for employee evaluations, making sure they capture the wide range of employee behaviors and traits a company wants, but eliciting opinions from the people who will become the new hire’s coworkers—particularly if they are incentivized for giving accurate predictions, instead of ones that conform to their own desires (perhaps they are lazy, and don’t want to bring in someone who will increase their own personal workload)—should improve the hiring calculus.

However, in speaking with the executive search consultant, we feel there’s also a use for screening employees, at least in the quantified forecasting realm.

Can you take an applicants metrics to provide a quasi "base rate” forecast for their expected performance? Can that information be provided in the final round markets to help team members give more accurate predictions?

The odds that these markets would be used solely in the hiring process seems nigh impossible. Politics, nepotism, corruption, desired ethereal attributes, and the limits of forecasting all stand in the way, as the executive consultant we spoke to said, as well as the head of HR at a Fortune 200 company. But hiring markets as an additional variable for managers to consider? Definitely worth prospecting.

Turning to deadline markets, Robin says:

Other examples [with the gold include], deadlines, famously.

Almost all organizations have projects with deadlines, and they do kind of want to know if they are going to make the deadlines…

It’s not just will you make the deadline, but what changes could change the chance to make the deadline? What personnel changes, priority changes, definition changes, feature requirement changes, etc.? Budget changes? How would they affect the deadline?…

[There are also problems where] people don’t really want to know if they’re going to make the deadline…

[But these] are exactly the kind of messy details that you need to work through.

—Robin Hanson, Take the Gold!

Dirty Job

The appeal of a forecasting social network, or a New York Times meets FiveThirtyEight, is clear. At scale, it’s a pretty attractive proposition, and would likely bring along with it status and prestige to whomever could make it happen. Or, think DraftKings or its competitor FanDuel, but with a larger event scope than just sports…it’s exciting and certainly lucrative!

And Hanson notes, prospecting in deadline, hiring, or other niche markets won’t be easy—or nearly as sexy.

All innovating is a combination of a few elegant ideas and a lot of messy details…

If you want to go for this gold, you need to be willing to take the time to work out these details about each particular applications…

And that’s what we haven’t seen so far.

—Robin Hanson, Take the Gold!

But there’s hope! There are some efforts to bring forecasting into corporate environments, such as the Confido Institute. As they write:

Forecasting and estimation tools are on the rise, but there are recurring reasons why they are not implemented in the biggest institutions. We aim to change that.

They do so by making it easy for companies to spin up their own internal prediction markets.

However, on first glance of their website and based on an early demo of their project at an Oxford forecasting conference in the summer of 2022, it doesn’t seem to be tackling the hard questions, and instead passes them on to companies to sort themselves.

WHAT’S YOUR TAKE?

Base Rate News: PMs in NYT & more

The Wager That Betting Can Change the World | New York Times | 10.8.23

🥩 Earlier this month, New York Times technology columnist Kevin Roose published what is likely the most mainstream portrayal of our community in recent memory after attending the Manifest conference hosted by Manifold Markets in Berkeley, CA.

🥔 After reading the article and sharing it with a few friends/colleagues outside of the forecasting space, we’re not sure that a random reader would be any warmer towards prediction markets from Roose’s account. They might understand the space better, and Manifold Markets got some fantastic exposure, so perhaps the article is still very much a net positive for the space. But we’re not sure. Let us know what you think on Twitter or in the comment section below!

Fortunately, Roose expanded on his NYT piece in his Hard Forks podcast, “a show about the future that’s already here.” Austin Chen covers the section on prediction markets in his LessWrong post here.

Lancaster University to open first prediction market for Atlantic hurricanes | Lancaster University | 10.3.23

🥩 The Climate Risk and Uncertainty Collective Intelligence Aggregation Laboratory (CRUCIAL), a joint initiative between Lancaster and Exeter Universities, has announced that it is opening its first prediction market to forecast the intensity and frequency of Atlantic hurricanes in the 2024 season.

🥔 As we covered in our last newsletter, predicting hurricanes is far easier than other natural disasters such as earthquakes because of the robust existing infrastructure and data around meteorology. But while perhaps an effort for harder-to-predict events would seem more high-impact, it is exciting to see forecasting applied to an area that we have identified as exceedingly critical.

Prediction Market 'Zeitgeist' to Use CoinDesk Indices for Broad Crypto Bets | CoinDesk | 10.5.23

🥩 Zeitgeist, a prediction market on the Polkadot blockchain, has announced that they will be using CoinDesk Indices as the subject of bets on the performance of two categories of cryptocurrencies.

🥔 We met the founders of Zeitgeist when we spoke at Consensus 2022 in Austin, TX and they seem like very bright guys. We were big fans of their platform, so it is exciting to see them partner with a big brand like CoinDesk and work to raise liquidity and volume. But as Robin Hanson mentioned, the real utility and roadmap here might be a hard sell.

e.g., Clay’s forecast on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine required hundreds of hours over a period of months, which only made logical sense as it was directly tied with his master’s thesis. However, the vast majority of predictions, even by great forecasters—by their own admission—are made in minutes, and the amount of time spent by superforecasters or others in tracking their multitude of forecasts can be measured by single-digit hours per week (as mentioned in Superforecasting and other relevant academic articles).

I fully agree with Robin Hanson: We have to put decisions front and center. Predictions and prediction markets are just the means to make better decisions.

Hiring is not the killer application in my opinion. Think about a colleague Kim who got hired two years ago. can you imagine the company does a poll "was it a good decision to hire Kim two years ago?" Yes or No? They will then publish the result company-wide and resolve some prediction markets based on that. As a European, that surely violates one or more laws here.

Deadlines look much more likely to me. Looking at the business around Agile, there already is a market for forecasting tools. For example, the Scaled Agile Framework suggests a "confidence vote" at the big planning meeting every two months. Turning that into a prediction market is only slightly more technical. Atlassian could build it into Jira. It feels like we are so close.

To contribute another idea: Fake news and fact checking seems to work well if the platform allows to setup prediction markets quickly. https://marketwise.substack.com/p/the-battle-against-fake-news-how

Outstanding! Both well sourced and well written!

Unfortunately, I doubt that this newsletter will make you even minimum wage, which is unfortunate because you two are so good at this. Problems: too narrow a news focus, and the overall falling trend of news media of all sorts.

The only contrary data I have found so far is The Bulwark https://www.thebulwark.com/, growing vigorously while still, like you, using Substack as its base platform. It includes in-person events, videos including live video events, and several newsletters. You two both have considerable talents for video and come across well in person, so this might be a way for you to buck the trends.

That said, I suspect The Bulwark still is losing money while growing. According to what I have read online, it is bolstered by donations even though it is not a nonprofit.

Thanks to Open Philanthropy, huge amounts of money have been donated to crowd-sourced forecasting entities. Now the spigot has turned off, and its allied EA is hemorrhaging participants and donations. Much if not all of this is in danger of clawbacks in the FTX bankruptcy case. I hope you are not at risk! Given the world of increasing hurt on your field, you might gain traction.

More bad news: the entire news media ecosystem is failing fast. See https://unprecedented.ghost.io/archive/news-crash/ for a deep dive into the data. See also the imploding display ad ecosystem here: https://www.therebooting.com/p/newsletter-moneyball

We are still working on BestWorld, currently conducting research into ways to automate creating a news aggregation system with a future emphasis, using crowdsourced forecaster rationales + stated probabilities as inputs. Clearly both journalism and crowdsourced forecasting are money-losing propositions, with rare exceptions on the journalism side only. So perhaps we are chasing a mirage.